Hello and welcome to this first post in a series on reinforcement learning! In this post we learn what reinforcement learning is. By doing so we will explore how it differs from supervised and unsupervised machine learning. We will become familiarised with what an agent is and get to know a bit more about the set up of a reinforcement learning problem. Concepts we will learn are: Agent, Environment, State, Policy, Reward and Value Function.

I hope you are as excited as I am to embark on this journey into the world of reinforcement learning. As always – make sure to grab a good snack and a hot brew of coffee before we plunge in. Welcome to the learning journey!

The Agent | Our Protagonist For The Story

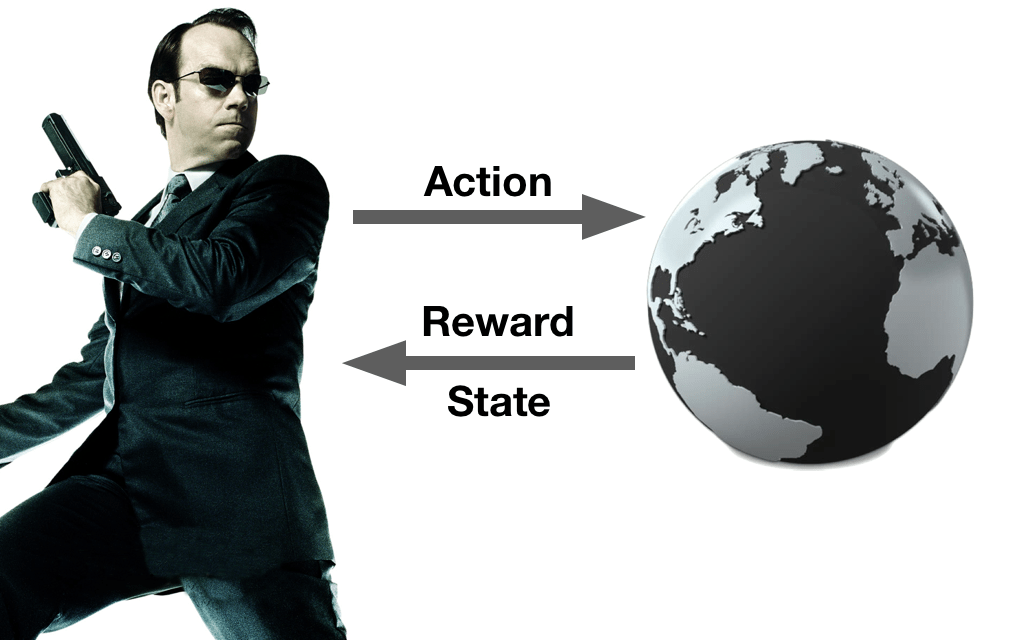

The learner in reinforcement learning is the agent. It’s called an agent because of the interactive nature of how the it learns. The agent acquires it’s own data by interacting with an environment that can be in one of several states. This interaction may or may not change the state of the environment, and and the environment responds with a reward signal. This interaction is shown in the image below.

The agent interacts with an environment. This environment can be either a simulated world such as a game or a computer model, or it can be the real world. To the agent it doesn’t matter as long as it can interact with it in the manner described by the image above. Each action the agent takes in the environment gives a response in terms of a reward signal (determined by a reward function) and a state. The state tells the agent something about the world and the reward tells the agent of whether that thing was good or bad. The goal of the agent is to interact with the environment in a manner which maximises the agents total reward.

It’s good to note that the agent itself isn’t necessarily excluded from the environment. For example the agent might have to eat in order not to starve. That means it has to observe it’s own internal state as well, and take actions accordingly.

Why Reinforcement Learning Is Different | Paradigms Of Machine Learning

In addition to reinforcement learning there are two other machine learning paradigms commonly used: supervised and unsupervised learning.

Supervised learning aims to find a mathematical function that maps an input space to a desired output space. That is, you have (labelled) data that you feed your learning algorithm. The algorithm then sees which what it should output and the algorithm finds an approximate mapping function – loosely explained. The objective here is for the algorithm to hopefully be able to extrapolate what it has learnt to new, unseen cases – and by doing so we say that it has generalised what it has learnt. This type of learner can be imagined as a student learning with the help of a supervising teacher – thus the name.

Unsupervised learning is different from supervised learning in that it has no labelled data. Instead the aim of such algorithms are to find relationships and differences, thereby learning the hidden structures in data. This type of learner can be thought of a student learning to tell cats and dogs apart by looking at droves of pictures and finding that some pictures look similar to each others. Note that the learner here actually never really learns what a “cat” or “dog” is or which is which. It only learns that one set of images looks a certain way and another set looks another way. In that sense, there is no target output for the unsupervised learner.

Now, one might observe from reading the above that both supervised and unsupervised learning are somehow… passive. The learner just learns from data collected in the past, that someone else collected. This is the main difference. As we saw above the reinforcement learning agent takes an active role in it’s learning. The agent, in a sense, creates it’s own data. This also means that the agent has to find a way to balance the explore-exploit dilemma (as talked about in the post on multi-armed bandits). A problem neither of the two other learning paradigms has to take into account as all the data is collected separately from the learning. Thus, the paradigms can be loosely surmised as follows:

- Supervised Learning: Learns by looking at examples in the form of data and corresponding labels. Learns explicit labels given by someone else. Goal is to approximate a mapping function from training data to specific labels while being as generalisable as possible.

- Unsupervised Learning: Learns by looking at raw data and figuring out how it is structured. Learns on it’s own from the data. Goal is to learn underlying or hidden structures in unlabelled data.

- Reinforcement Learning: Learns by interacting with the data source. Learn in conjunction with an environment through feedback in the form of rewards. Goal is to maximise rewards.

Fundamental Aspects of Reinforcement Learning | The Three Elements And An Option

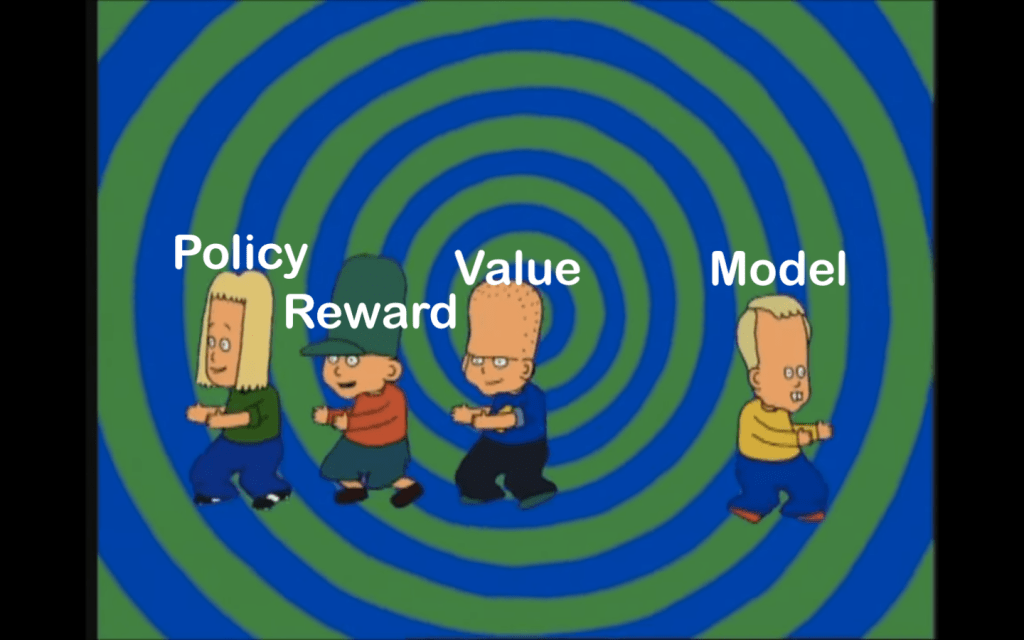

In addition to an agent and an environment, there are three fundamental components required to properly set up a reinforcement learning problem. These are a policy to govern the agent’s actions, a reward signal to help the agent learn what is good and bad, and finally a value function that indicate the long-term desirability of particular states. A fourth, optional part is a model of the environment, which allows the agent to test out ideas in the model before testing them in the environment – akin to how we humans plan by imagining how something will be.

1: A Policy

The policy of an agent is the same as the strategy of the agent. It’s a function that help the agent map from the current the state to which actions to take. In the previous post on multi-armed bandits we were introduced to our very first policy – the Epsilon-Greedy algorithm. The policy works by randomly choosing to either explore by taking any of the actions available to it or to exploit take the action with the currently highest perceived value. Since the multi-armed bandit is an environment with only a single state, the algorithm don’t have to take state into consideration since it won’t change. The Epsilon-Greedy is an example of a stochastic policy.

2: A Reward Signal

The reward signal defines the short-term objectives of the agent and shapes what behaviour the agent will learn. For each time step the environment will send the agent a reward signal. This signal is in the form of a single positive or negative number, indicating if something positive or negative happened.

It’s important to note that the reward signal is based on the immediate situation of the agent. This helps the agent learn actions with immediate effect very easily. But actions whose effect appear much later becomes harder. For example a student failing her exam because she didn’t study for it might experience a strong negative reward when she realises that she failed the exam. Here the reward signal is based on the current state of the environment (exam failed), but the actions leading up to it (didn’t study) all were taken in the past few weeks. In such a case it might be hard to understand why the student reached this bad state since the last actions she took were all mundane (wake up, eat breakfast, go to school). Therefore the agent also needs a value function in order to plan ahead.

3: A Value Function

The value function is a function that computes the total future expected reward of any given state, from that time step forward. This total expected reward is the value of that state. Whereas maximising reward is taking actions to maximise happiness in the immediate here and now, maximising value is taking actions to maximise happiness over the long term. You can thing of the value function as the method by which an agent plans ahead.

Let’s imagine that we have an agent with 300 dollars left at the end of the month. The agent seeking to maximise reward (here and now) might spend the 300 dollars on buying a nice dinner (or setting out on a drug-induced haze of hedonistic pleasures in Las Vegas). The agent seeking to maximise value on the other hand might spend the 300 dollars on a retirement savings account, on getting out of debt or on learning a useful skill.

In reinforcement learning we are generally much more concerned with maximising the value (total reward) rather than the immediate reward. The reason being that the rewards in themselves are (generally!) only small treats given along the way of teaching the reinforcement learning agent a larger goal.

The problem with maximising the value is that it very quickly becomes a hard problem. It is hard for two reasons. It is hard both because predicting the future is hard (as we ourselves know from our own lives) but also because we might not always realise how the agent will interpret long-term value. A very good example of this is the game CostalRunners 7 where boats race to finish the track. Along the way there are power-ups the boats can collect. Here the learning agent was supposed to learn how to race a boat along different tracks in a game and finish first. For us it is obvious that the long-term value for the agent is to learn how to race through the track as fast as possible while also collecting power-ups. But given how the rewards from power-ups were designed the agent’s value function caused it to get stuck in a loop collecting re-spawning power-ups. I guess that this is the AI equivalent of going on a cocaine-induced spending spree in Las Vegas… throwing everything away for short-term pleasure?

4: A Model Of The Environment

While every (proper) reinforcement learning has to have the three above in some form or another, it’s optional for learning agents to have a model of the environment. Thus, we can divide agents into two main types: model-based agents and model-free agents.

The model-based agents are agents who learn about the environment and who simultaneously builds a model of it. This might include the physics of the environment or the presence of other agents (as well as possibly the other agents’ own models). Such a model helps the agent predict what reward an action will produce. These models allow the agent to plan-ahead by imagining consequences of actions before they take place. This is in stark contrast to the model-free agent that does not have a model in which to test out ideas before actions are taken. The model-free agent is entirely based on trial-and-error. It is more like an animal acting out on pure instinct built from previous experiences, without any planning ahead. Of course, agents exist on a spectrum and can have more-or-less complete models.

Wrapping Up

In this post we’ve learnt what reinforcement learning is and how it differs from the other machine learning paradigms. We were introduced to how reinforcement learning works on a high-concept level: An agent interacts in an environment that can have different states. The agent takes actions according to it’s policy. The environment responds by giving back a reward signal and whether the state changes. The goal of the agent is to maximise the total reward. This is predicted with the help of a value function. To it’s help the agent might have a model of the environment in which case it’s called a model-based agent, else it is called a model-free agent.

Okay, that was it for this first brief overview! I hope you enjoyed it. This post is intentionally very concept oriented, so if some things doesn’t make complete sense yet or it’s not obvious how a concept would work in practice don’t worry – we will do technical deep dives and test out these theories and techniques in future posts! In the meantime until those posts, take care and until next time, stay hungry for knowledge!